A short interview with Sjón about his latest novel

In your new novel Mánasteinn – Drengurinn sem aldrei var til (Moonstone – The Boy Who Never Was) a variety of threads are traced, disparate threads that nevertheless knit really well together in this unique story. What inspired this work?

SJÓN: For many years I had been collecting material about the three elements that form the backdrop to the story of Máni Steinn – the Spanish Influenza epidemic which reached Iceland in the autumn of 1918, Icelanders’ interest in films right from the birth of cinematography, and the history of homosexual people in the microcosm that is Reykjavík – but I could never see a way to make use of it, neither in combination nor individually. Not until I had the idea of placing a young boy in the middle of the Spanish Influenza epidemic, a boy who, because of his situation, watches events from the outside, and is not emotionally traumatised like other townspeople whose close relatives and friends were dying. I then realised that of course he was crazy about the cinema, which made it possible for me to interweave that with his real life. But the reason for his being an outsider in society was missing for a long time, which meant that I couldn’t make much progress apart from working on the usual research I always do when I’m writing.

And then I read the novel “A Life Apart” by Neel Mukherjee, and I realised that Máni Steinn was gay, like the central character in that book. When that bit of the jigsaw fell into place, the story appeared before me remarkably clearly, and it took me much less time to write than I had thought it would.

Factual material provides to some extent the basis for all your books. Did you have to do a lot of research when you wrote this book?

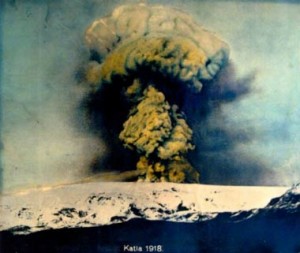

SJÓN: Yes, I ploughed through all that’s been written about the Spanish Influenza epidemic and the history of gay people in Iceland; in both instances remarkably little has been written to date. I read whole volumes of contemporary newspapers in order to get the “vision” of those who were alive at that time, in the same sort of way I did with both Skugga-Baldur (The Blue Fox) and Rökkurbýsnir (From the Mouth of the Whale). I also researched cinema culture in Reykjavík up to 1919; hardly anything had been written about that, and it surprised me how many good films were shown during those early years of the full-length feature film. For instance, during the very cold year of 1918 ninety films were imported, so that every three days a new film was premiered in one of the two cinemas in the town, whose inhabitants at that time numbered fifteen thousand.

Finding the original titles of these movies took a lot of effort, because most of them came to Iceland via Denmark, where they had been given Danish names. And I watched as many of them as I possibly could. Since then I have become an even greater fan of silent films, which were certainly not just silent and black-and-white, because they were always accompanied by music and were often in colour. The recent rekindling of interest in this unique art form, which has more in common with poetry and dance than other narrative forms, is a great source of joy to me.

The scenery of the age in the book is vast and dramatic – the Katla volcano spits out fire and brimstone, the Spanish Influenza epidemic kills thousands of people, the Great War rages in the world outside, and the Icelandic nation prepares to become an independent state. These are portentous times, it is in fact a world that has fallen apart, and yet it has much relevance for us today – a classic theme.

SJÓN: I really enjoy working with opposites and extremes. Most of my novels feature confrontations between contrasting ideologies, along with an examination of the lot of individuals caught up in such periods of unrest. In Mánasteinn the cultural world of the “Saga nation” meets the narrative form of the movies, and there is at least one person who hears the call of the age in this brand new art form. But Iceland’s history is mostly the story of an island that lies to the north of wars, and the moments when its history converges with that of the big world beyond its shores are so rare that a novelist can’t let an opportunity like that pass by.

To what extent is Máni Steinn’s story a true story?

SJÓN: Of all the characters I have created, Máni Steinn is in many ways the closest to me. His character and his interests have much in common with the adolescent I once was – the rebellion, the movie mania, being at odds with society – and this is epitomized in his interest in Louis Feuillades’ exciting serial film Les Vampires about a criminal gang known as “The Vampires”. Feuillades’ films were extolled by the surrealists, and here Máni and I come together, discovering for instance René Magritte and Robert Desnos, who exploited his work in their pictures and poems. The book actually begins with a fantastic poem by Desnos, Under Cover of Night, which became a great inspiration for me when I was trying to find the right tone for the narrative. Apart from the fact that Máni’s fate is tougher than anything I’ve ever had to experience, we also differ in that he is gay and I’m not.

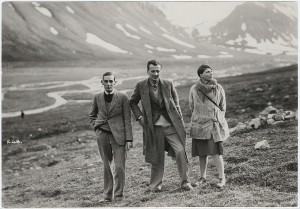

Another “true” event in the story occurs in the final chapter, where three significant figures appear in supporting roles, the poets Robert Herring and Bryher, and the cinematographer and editor Kenneth MacPherson, who travelled together to Iceland in 1929 in order to make a film. These three turning up in our little capital in the North were representatives of world culture both in art and in life, as Bryher was married to MacPherson and at the same time they were both having affairs with the American poetess H.D. It was a great moment when I came across records of that visit, because it allowed me to sum up many of the novel’s main subject matters.

And, as the reader discovers at the very end, the emotional and moral urgency behind telling the tale of Máni Steinn comes from the novel being dedicated to the memory of my uncle Bósi who died of AIDS in 1993.

You have been quoted as saying that in all your novels you are mainly dealing with the same main theme: Being a decent human being is very difficult. Does the same apply to this particular book?

SJÓN: Absolutely. Fate and his fellow men have pushed Máni Steinn to the fringes of society, and he feels he will always be a spectator, looking at other people’s lives. But when Reykjavík’s darkest hour strikes the city and its townspeople, he feels compassion for them and emerges as a more complete human being than before. Whether his reward turns out to be anything more than an increased understanding of himself is not at all certain. But as long as there is something exciting on in the cinema, and adventures of the night beckon, our protagonist is at peace with his life. And so should we be, too.

Moonstone – The Boy Who Never Was was published by JPV in Icelandic in 2013. The foreign rights have been sold to Farrar, Straus and Giroux (US), Sceptre (UK), S. Fischer Verlag (Germany), Rivages (France), De Geus (The Netherlands), C&K (Denmark), Alfabeta (Sweden), Dybbuk (The Czech Republic), LIKE (Finland) and Sproti (The Faroese Islands).